None of the three Guineas is thriving, but in Guinea-Bissau, the country that sits on Africa’s map like a tongue of fire, recent events are twisting that nation’s fate into profound misery.

Guinea Conakry is in the grip of a military dictatorship with a messianic complex, while Equatorial Guinea is led by an authoritarian civilian government that has lost its way.

Now, Guinea-Bissau, the country that gave the world Amilcar Cabral, one of Africa’s most foresighted revolutionaries, has added manufactured military coups to its long list of notoriety, which includes being one of the continent’s most deadly drug routes.

Making a coup

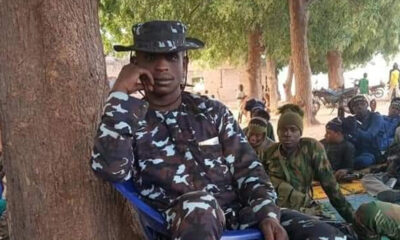

On November 26, a military regime led by General Horta Inta-A deposed the elected government of President Umaro Sissoco Embalo. It moved to consolidate its grip on power by appointing Finance Minister Illidio Viera Te as the country’s new prime minister. However, not many who have been following events in the small West African country (with a population of two million) would be impressed by the whitewash.

The deposed government of Embalo was obviously being clever by half by fomenting a palace coup ahead of the announcement of the election results, which might not have favoured him. Embalo has fallen the way he rose. In 2020, he literally defied the electoral commission after the elections and announced himself president from a hotel in the country’s capital, Bissau.

After two successful military coups, over half a dozen failed ones, and intermittent power struggles between the military, politicians, and drug barons who have made Guinea-Bissau a key corridor to Latin America and Europe, citizens in that country, one of the world’s poorest, were ready to give Embalo a try.

READ ALSO:

- Siyan Oyeweso: Lessons in virtue and vanity

- Court Rules Only Lawyers Can Represent Nnamdi Kanu, Rejects Brother’s Appearance

- Imo Economic Summit: Aliko Dangote Vows to Become State’s Largest Investor

He started well, under the rallying cry of “Embaloism,” which was supposed to rid the country of corruption, poor governance and instil discipline. He also attempted to rebuild confidence with regional allies and powerhouses, including Nigeria, and subsequently reached out to Portugal and the IMF to repair the country’s badly damaged economy.

From Embaloism to Embalomylitis

However, it didn’t take long before Embaloism gave way to Embalomylitis, a condition that has left citizens poorer and poorer, eventually ranking 177th out of 191 on theUN Human Development Index.

Embalo prioritised conspicuous consumption. According to a DW report quoted by opposition figures, the deposed president made over 300 trips abroad in five years, accumulating more than 200 flights on a private jet for non-state visits.

This was a time when schools were failing, and roads and hospitals were in disrepair. Two years ago, his finance minister and treasury secretary were also accused of withdrawing $10 million of state funds, which was paid into 11 private companies linked to a pro-government coalition. Yet, Emabloism was supposed to fight corruption.

To cover his tracks and maintain his hold on power, Embalo went the extra mile to look after the military, often using diverted resources, which primarily came in the form of foreign aid and donor funds, to keep soldiers happy.

The crunch

Matters came to a head last year when Embalo’s government shifted the elections, which were initially scheduled in November, ahead of February 2025, when his constitutional five-year first term limit was due to expire.

One year after the initial election date, and 10 months after his first term expired, Embalo finally organised an election last month, but lacked the courage to wait for the results before he instigated a coup led by two of his key allies – a General and a politician who were both members of his kitchen cabinet.

READ ALSO:

- NSCDC rejects VIP protection requests from senators as demand surges after police withdrawal

- Edo Assembly Moves to Arrest Obaseki, Others Over MOWAA, Radisson Hotel Probe

- Three Top Contenders to Replace William Troost-Ekong as Super Eagles Captain

In one of the most dramatic military take-overs, the fallen president was speaking to the press as troops were announcing his removal, and hours later, he was safely in Dakar, Senegal, which had been like his second home. The demand of the leader of the opposition, Domingos Simoes Pereira, and the ECOWAS election monitors, led by Nigeria’s former President Goodluck Jonathan, for the full results to be released, has so far been ignored.

Dancing on Cabral’s grave

Cabral would hardly recognise Guinea-Bissau as the Portuguese colony he fought so bravely for, and for which he left a legacy that significantly influenced the independence struggles of liberation groups such as the ANC, FRELIMO, SWAPO and MPLA. In his book, Tell No Lies, Claim No Easy Victories, he extolled the virtues of honesty and accountability. Internal forces that couldn’t stand his courage and independence, instigated from outside, killed him on the eve of that country’s independence.

Yet, five decades later, the more things appear to have changed, the more they look the same. Across the continent today, from Bissau to Conakry and Malabo, and from Niamey to Ouagadougou and Bamako, Africa is experiencing an upsurge in military regimes, all claiming a lack of honesty and accountability for striking. Yet, none of the usurpers is showing any different habits from the politicians they overthrew.

If you add the military coups in Sudan, Gabon, and Chad to the list, and exclude the numerous other failed attempts, the picture begins to resemble a throwback to Africa of the 1980s and early 1990s.

The democratic space, even in once politically stable havens such as Côte d’Ivoire and Tanzania, is shrinking, and successful transitions after elections are becoming the exception rather than the rule. In Cameroon, 92-year-old President Paul Biya, who has been in power since 1982, contested and won reelection, despite being unaware that he was on the ballot, let alone that he had been reelected for the eighth time.

READ ALSO:

- Ned Nwoko vows legal action against rising online harassment, criminal defamation

- Senate Launches Emergency Probe into Widespread Lead Poisoning in Ogijo, Lagos/Ogun

- Court of Appeal Affirms Ruling Barring VIO from Seizing Vehicles or Fining Motorists

Another Africa

In another life, some of the continent’s strong leaders, such as Nigeria’s President Olusegun Obasanjo, Senegal’s Abdou Douf, Ghana’s Jerry Rawlings or South Africa’s Nelson Mandela, would have weighed in, as Obasanjo did in Sao Tome and Principe in 2003, to call the soldiers to order.

But it’s different today. Not only is the continent buffeted and weakened by severe economic, security, and political challenges, poor governance has also worsened the situation. The West African regional group, ECOWAS, which would have been the first line of defence in Guinea-Bissau, is fractured, sundered by the new alliance of three delinquent Sahelian states – Mali, Niger, and Burkina Faso.

Africa cannot help itself, nor can it rely on traditional Western allies, especially in Europe. France, for example, has fallen out of favour in several Francophone countries, while the US, under President Donald Trump, is setting the worst example of chaos-based leadership.

On your own

Guinea-Bissau can only expect messages of condemnation and threats of isolation from ECOWAS, the AU, and the UN. Such messages hold no weight for Embalo and his cohorts. They have heard similar rhetoric many times before without consequence.

The risk in Guinea-Bissau is unlikely to prompt Portugal, the country’s former colonial power, or interest the world’s resource vultures or its warmongers, such as China and Russia. Bissau-Guineans are on their own. The world would hardly notice until the tornado of military coups makes landfall in another African country, which, sadly, may be sooner than later.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login