International

Young men trapped between war and conscription in Myanmar’s Rakhine

Young men trapped between war and conscription in Myanmar’s Rakhine

Since war resumed in his native Rakhine State last November, Thura Maung has seen his options narrow.

The 18-year-old, from the state’s ethnic Rakhine majority, first fled his home in the coastal town of Myebon in December, when clashes between the military and autonomy-seeking Arakha Army – formerly known as the Arakan Army – seemed imminent.

He and his family escaped by boat, travelling along river inlets at night to avoid being seen by the military. They returned a few days later, but fled twice more over the following months as the fighting escalated.

By February, the military and AA were battling for control over Myebon, and Thura Maung could hear shelling from the village where he had taken shelter. The military had also blocked the movement of goods and shut down the internet in areas affected by the conflict, leaving his family struggling to make ends meet.

With his university effectively closed due to the fighting, he felt his dreams slipping away. “There were no opportunities for my life to develop, and I saw no future,” he said.

It’s a feeling shared by Zubair, an ethnic Rohingya from Rakhine State’s northern Maungdaw township. The 24-year-old was doing an internship with a civil society organisation focused on peacebuilding when the fighting broke out and his office closed.

Soon, he was running from the war as well as a military conscription drive targeting Rohingya men. “We weren’t able to stay at home, go to work or even sleep on time,” he said. “Time that we could’ve spent working on our futures was wasted.”

Zubair and Thura Maung are part of a new generation of young people across Myanmar whose lives have been turned upside down by the 2021 military coup. In Rakhine State, people had already lived through years of communal conflict and a brutal 2017 military crackdown on the mostly Muslim Rohingya. The escalating violence between the military and AA has only made matters worse, according to Karen Simbulan, a human rights lawyer specialising in conflict sensitivity in Rakhine.

READ ALSO:

- Varsities workers threaten fresh industrial action over withheld salaries

- JUST IN: Court quashes dethronement of Emir Bayero, others

- BREAKING: Court scraps Ondo LCDAs

“With the most recent renewed fighting and the looming threat of forced conscription, many who had persisted and stayed in Rakhine despite everything are seeing their futures taken away from them,” she said. “Many are taking significant risks to flee to safety, often putting themselves in highly vulnerable situations just to survive.”

Al Jazeera spoke with four young men from Rakhine State about the effects of the conflict on their lives. They have all been given pseudonyms to protect their safety.

‘Stirring up communal tensions’

The renewed fighting is the latest crisis to hit Rakhine State, home to Daingnet, Mro, Khami, Kaman, Maramagyi, Chin and Hindu minorities as well as the Rohingya, and the mostly Buddhist Rakhine majority. A category four cyclone hit the region last May, following successive waves of violence in the decade leading up to the coup.

In 2012, mobs of ethnic Rakhine and Rohingya people attacked each other with sticks and knives and burned each other’s homes, leaving dozens dead and some 140,000 forced from their homes. Afterwards, the military imposed tough restrictions on Rohingyas’ movement and access to services, while continuing to deny them citizenship under a discriminatory 1982 law.

The situation deteriorated dramatically in 2016 and 2017 when the military killed thousands of Rohingya civilians and committed widespread sexual violence and arson following attacks on military outposts by a Rohingya armed group. Its “clearance operations” in northern Rakhine State drove more than 750,000 people into neighbouring Bangladesh, and the crackdown is the subject of continuing genocide proceedings at the International Court of Justice.

The AA stepped up its fight for autonomy in late 2018; over the next two years, Rakhine State endured some of the most intense armed clashes seen in Myanmar in decades. The military also indiscriminately bombed and shelled civilian areas, committing what Amnesty International identified as war crimes.

The military and AA reached an informal ceasefire in November 2020, just three months before the generals seized power from the elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi. Weeks later, the military cracked down on peaceful protests across Myanmar with gunfire and arrests. An armed uprising soon followed; by mid-2021, all-out war had erupted across the country.

Existing ethnic armed organisations trained and fought alongside anti-coup People’s Defence Forces (PDF), but the AA mostly stayed out of the fray, instead focusing on establishing governance mechanisms in its territory through its administrative wing, the United League of Arakan.

That changed last October, when the AA joined ethnic armed groups fighting on Myanmar’s eastern border with China to launch Operation 1027 declaring their intent to eradicate “oppressive military dictatorship”. Within weeks, they had seized strategic territory and other resistance groups were launching new offensives across the country. On November 13, the AA brought the war to Rakhine soil with coordinated attacks on military positions.

READ ALSO:

- 1 killed, 2 policemen injured as hoodlums unleash mayhem in Kano

- Court remands 11 persons over alleged cultism, robbery in Lagos

- Binance: India slams heavy fine on crypto firm for non-compliance

The AA and its allies have since driven out the military from most of central and northern Rakhine State as well as Paletwa township in neighbouring Chin State. Following tactics it has long used to punish communities harbouring armed resistance, the military has retaliated with full-scale attacks on AA-controlled and contested areas by air, land and water while cutting off transit routes, communication channels and access to medical care for entire populations.

Hundreds of civilians have been injured or lost their lives and more than 185,000 people displaced across Rakhine State and Paletwa since November out of more than three million that the United Nations says have been displaced across the country, mostly as a result of the coup.

Through its forced conscription of Rohingya men as well as by demanding they protest against the AA, the military is also deliberately working to threaten years of fragile progress towards reconciliation between Rakhine and Rohingya communities, according to Simbulan, the conflict sensitivity specialist.

“The military is once again resorting to stirring up communal tensions because it is desperately losing ground in Rakhine,” she said. “As the expected de facto authority in Rakhine, the AA needs to heed its own words that this is a military tactic to divide communities, and not fall into the trap the military has set.”

Fear of conscription

Zubair, in Maungdaw, said that the conflict and military conscription drive left him feeling like the military was attempting to “destroy our Rohingya youth … from every angle”.

Since November, he has repeatedly been forced to flee his home due to the conflict. “Our village was attacked a lot, so we moved to another village which was less attacked,” he said. By February, he was also running from military conscription. Human Rights Watch reported in April that the military had used methods including false offers of citizenship, nighttime raids and abduction at gunpoint to conscript at least 1,000 Rohingya men, some of whom it sent to fight on the front lines against the AA.

In Maungdaw, Zubair said he had been unable to sleep since military soldiers took his neighbours from their home one night in March because he was fearful he might be next. The military was also blocking the roads between villages, leaving him and other young people with few places to go. “We ran inside the village,” said Zubair. “When we heard that [soldiers] were coming from one direction, we ran in another.”

Then, the military ordered the Maungdaw hospital to close, leaving Zubair’s father, who needs to use an inhaler because of a respiratory disease, unable to access medical care.

By April, heavy fighting between the military and AA had reached Rakhine State’s northern townships, alongside a series of devastating arson attacks across neighbouring Buthidaung township whose perpetrator remains disputed.

With a fight for control over Maungdaw looming, Zubair and his parents sneaked across the Naf river into Bangladesh one night at the end of May.

Now staying in the world’s largest refugee camp, Zubair rarely leaves his shelter, fearing that he could be robbed by other camp residents or arrested by Bangladeshi police, who sent back more than 300 people between February and April, according to the research and advocacy group Fortify Rights.

READ ALSO:

- 34 die, scores hospitalised after taking alcohol in India

- JUST IN: Lagos: 21 people die in fresh 401 cholera cases

- Court postpones ruling on Kano Emirate tussle

“I need to be cautious every time I go outside,” he told Al Jazeera.

After escaping to nearby villages, Thura Maung, the Rakhine youth, also left the state due to the conflict. On February 9, he travelled by boat for two days to the state capital of Sittwe, and then boarded a plane bound for Myanmar’s largest city of Yangon.

He landed to find a city in chaos. While he was in transit, the military had announced plans to activate conscription from April, prompting a mass exodus from areas under its control. Thura Maung, who had planned to enrol in language classes in Yangon, could not find a course accepting new students and also feared conscription himself. So a week later, he began the trip back to Myebon, which had just been captured by the AA.

As soon as his flight touched down in Sittwe, however, he was arrested at the airport along with the other passengers on his flight. Held without charge at a Buddhist religious centre, military soldiers took his mugshot, interrogated him and searched through his phone.

He is among hundreds of people who have been detained by the military while travelling to or within Rakhine State since February. In March, the military also ordered travel agents and bus operators to stop issuing tickets to Rakhine State natives.

While these actions may have been intended to stop the flow of information and recruits to the AA, for Thura Maung, they had the opposite effect. Nearly a week after he was arrested, he sneaked away and headed towards an AA camp. “I felt lost,” he said. “I attempted to enter the AA without letting my parents know, because I thought it was the only certain thing I could do.”

A relative talked him out of it, however; now back in Myebon, where he is safe from military conscription because the AA controls the town, he still fears he could become the next victim of the military’s attacks. “I feel safer living in Myebon, but I still have to worry about air strikes,” he said.

‘Survival is my priority’

Tun Tun Win, a 24-year-old ethnic Rakhine, was also arrested at Sittwe airport. He had been attending language classes in Yangon when fighting broke out between the military and AA; although he had initially stayed in the city, he changed his plans in February. “Although there is ongoing conflict in Rakhine, I felt more secure living with my family than living alone in Yangon under the conscription law,” he said.

READ ALSO:

- Presidency responds to Aisha Yesufu’s allegations regarding Tinubu in S’Africa

- Negotiator killed after delivering N16m ransom, 3 bikes to bandits in Kaduna

- Arsenal ditches Osimhen for Girona’s Dovbyk as NFF denies banning Napoli strike

Fleeing one danger, however, he was soon caught up in another. Like Thura Maung, soldiers took him away at the airport and interrogated him for several days at a Buddhist religious centre before he managed to sneak away. Now back home in Myebon, he faces a new set of struggles. “Currently, survival has become my priority rather than pursuing my ambition and plans,” he said.

Arkar Htet, a 27-year-old ethnic Rakhine from a village on the outskirts of Sittwe, also saw his plans fall apart after the conflict broke out. He was running an online delivery service and working as a dance instructor but stopped both after the military imposed a nighttime curfew and stepped up its surveillance and arrests. “I feared going outside even in the afternoon,” he said.

But even at home, he did not feel safe. As the military and AA battled for control over the town of Pauktaw, 30 kilometres (19 miles) northeast, military shells whizzed over his roof, as well as jet fighters on their way to bomb the town.

By January, the AA controlled Pauktaw, but the military had burned most of it down. As the fighting shifted to areas around Sittwe, Arkar Htet and his family fled by boat on February 29. Stray fire injured a passenger on the way; back in the city, about a dozen people died when shelling hit a portside market.

Arkar Htet and his family managed to reach a village under the AA’s control in Ponnagyun township, and in early April, he told Al Jazeera that he felt “70 percent safe”.

Less than two months later, on May 29 and 30, the military raided Byaing Phyu village, just a few kilometres from the village from which Arkar Htet had fled. According to the AA, military forces killed 72 civilians and raped three women; the military has denied the claims.

Then on June 1, the military bombed a village in Ponnagyun township next to the one where Arkar Htet had taken shelter, killing two civilians. Al Jazeera has been unable to get in touch with him since.

Young men trapped between war and conscription in Myanmar’s Rakhine

International

UK Court Hands Life Sentence to Nigerian Teen for Knife Attack Killing

UK Court Hands Life Sentence to Nigerian Teen for Knife Attack Killing

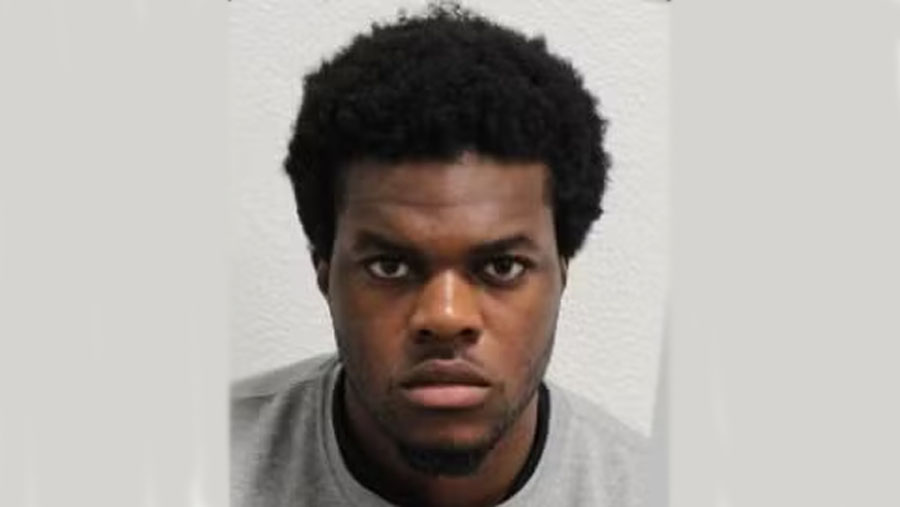

A Nigerian teenager residing in the UK, Jackson Uwagboe, has been sentenced to life imprisonment for the murder of 21-year-old Robert Robinson, following a brutal knife attack in Lewisham, London. The sentencing was delivered at the Old Bailey on Wednesday.

The Metropolitan Police confirmed that 19-year-old Uwagboe of Hamilton Street, Lewisham, was found guilty of murder on Tuesday, 10 February 2026, in a case stemming from a dispute over a stolen bicycle. The court ruled that Uwagboe must serve a minimum of 21 years before he can be considered for parole.

Uwagboe’s co-defendant, Eromosele Omoluogbe, 24, was earlier convicted of perverting the course of justice after assisting Uwagboe in attempting to flee to Nigeria via Heathrow Airport.

READ ALSO:

- Ogun Gov Rewards Nigeria’s Best Primary School Teacher with Car, Bungalow

- Police Bust Gang Armoury, Arrest Two Suspects in Delta

- Peter Obi Launches ‘Village Boys Movement’ to Rival Tinubu’s City Boys Ahead of 2027

Prior to this sentencing, two other men, Ryan Wedderburn, 18, and Kirk Harris, had already been convicted and handed life sentences in May 2025 for their roles in the same murder.

Detective Inspector Neil Tovey, who led the investigation, described the incident as a “brutal and sustained attack”. He said, “Robert was subjected to a brutal and sustained attack by a group of men armed with knives. He was unarmed, already wounded, and on the ground when Uwagboe attacked him. Today’s verdict brings justice for Robert Robinson and his family.”

The case has drawn attention to youth violence, knife crime, and gang-related activity in London, as well as the challenges faced by law enforcement in preventing violent disputes over seemingly minor disputes such as bicycle theft.

The sentencing underscores the UK judicial system’s approach to serious violent crimes, ensuring that perpetrators face long-term incarceration while providing a clear minimum term before parole consideration.

UK Court Hands Life Sentence to Nigerian Teen for Knife Attack Killing

International

UK-Based Nigerian Gets 13-Year Jail Term for Forcing Girlfriend to Abort Pregnancy

UK-Based Nigerian Gets 13-Year Jail Term for Forcing Girlfriend to Abort Pregnancy

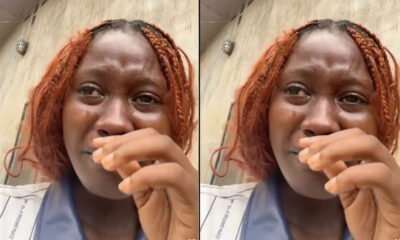

A UK-based Nigerian man, Adeleke Adelani, has been sentenced to more than 13 years’ imprisonment for unlawfully aborting the pregnancy of his former partner after coercing her to take abortion medication on Valentine’s Day.

The offence occurred in 2020 when Adelani, then 28 years old, deceptively invited the woman — whose identity is legally protected — to his residence in Letterkenny under the guise of discussing the future of her pregnancy. Evidence before the court showed that the victim was nine weeks pregnant at the time of the incident.

Prosecutors told the court that upon her arrival, Adelani threatened the woman with violence and forced her to ingest five tablets of misoprostol, a drug used for medical abortions, thereby causing the unlawful termination of the pregnancy. The court heard that the defendant had researched the medication in advance and acted deliberately. The victim later contacted authorities, leading to Adelani’s arrest by Irish police.

READ ALSO:

- Lawmaker Jailed for Mocking President in Facebook Post

- Police to Arrest TikToker Mirabel After She Recants False Rape Claim

- Tinubu Reduces Reliance on U.S, Strengthens Defence Partnerships With Turkey, EU

At the time of the sentencing, Adelani was already serving a separate seven-year prison sentence for an unrelated offence. He had initially been due to stand trial last year but pleaded guilty before jury selection began, accepting responsibility for the charges brought against him.

During the sentencing hearing at the Letterkenny Circuit Court, the victim delivered a powerful impact statement, explaining that although she had chosen to forgive Adelani, the consequences of his actions would remain with her for life.

“I have forgiven the defendant,” she told the court. “That forgiveness does not mean what he did was acceptable. It means I refuse to let what he did continue to control my heart and my life. When he wrongfully imprisoned me and caused the termination of my nine-week pregnancy, he took far more than my freedom. He took my child. He took my sense of safety. He took a future that I had already begun to plan and love.”

In a letter read aloud in court, Adelani apologised to the victim, accepted full responsibility for his actions, and expressed remorse for the pain and trauma he caused.

Delivering judgment, John Aylmer described the crime as deliberate, premeditated, and deeply traumatic, stressing that it involved coercion, abuse, and a serious violation of trust. The judge sentenced Adelani to 11 years in prison, with the final two years suspended, for causing the unlawful termination of a pregnancy, and an additional five years, with the last 12 months suspended, for assault causing harm.

The sentences are to run concurrently, adding to Adelani’s existing term and resulting in an overall prison sentence exceeding 13 years. The case has reignited debate in Ireland and internationally about reproductive coercion, domestic abuse, and violence against women, with legal observers describing it as one of the most serious cases of its kind in recent years.

UK-Based Nigerian Gets 13-Year Jail Term for Forcing Girlfriend to Abort Pregnancy

International

Epstein, Ex-Israeli PM Named in Alleged Profiteering From Boko Haram Crisis

Epstein, Ex-Israeli PM Named in Alleged Profiteering From Boko Haram Crisis

A new investigative report by Drop Site News has alleged that the late American financier Jeffrey Epstein and former Israeli prime minister Ehud Barak leveraged Nigeria’s long-running Boko Haram insurgency to pursue commercial, security, and strategic interests in the country.

According to the investigation, emails released by the United States Department of Justice in 2018 show Epstein acting as a behind-the-scenes facilitator in discussions involving Jide Zeitlin, then chairman of Nigeria’s Sovereign Investment Authority, and Sultan Ahmed bin Sulayem, former chairman of DP World. The exchanges allegedly focused on attempts to secure control of key shipping terminals in Lagos and Badagry, following unsuccessful negotiations with successive Nigerian administrations dating back to 2005.

The report claims DP World was unwilling to invest in a proposed industrial zone in Nigeria without full or majority control of the adjoining port infrastructure, a demand that reportedly stalled the deal for years. Epstein, who died in a New York jail in 2019 while awaiting trial, is alleged to have helped revive talks by brokering introductions and strategic conversations.

READ ALSO:

- CBN Policies, Foreign Inflows Drive Naira to Two-Year Peak

- Edo Governor Okpebholo Names Mercy Johnson-Okojie Special Adviser

- Many Feared Dead as Suspected Lakurawa Militants Attack Kebbi Communities

Drop Site News further reported that bin Sulayem resigned on February 13 after renewed scrutiny of his past links to Epstein resurfaced publicly, intensifying attention on the historical port negotiations and the role of foreign intermediaries in Nigeria’s maritime sector.

Beyond logistics and port infrastructure, investigators highlighted what they described as near-daily correspondence between Epstein and Barak after the former Israeli leader left public office. Barak, who served as Israel’s defence minister until 2013, allegedly sought to deepen Israeli-Nigerian security cooperation, using Nigeria’s counter-insurgency battle as an entry point for Israeli-linked security, energy, and technology investments.

The report said Barak later relied on security networks in Nigeria to promote Israeli defence and surveillance firms. In 2015, Barak and a partner invested $15 million in FST Biometrics, founded by former Israeli intelligence chief Aharon Ze’evi Farkash. The firm’s Basel biometric system, originally deployed at Israel-Gaza crossings, was subsequently marketed in Nigeria as a counter-terrorism solution.

According to the investigation, the biometric technology was introduced at Babcock University as protection against Boko Haram threats, while also being pitched to African governments for broader identity management and population-control applications.

The report further cited a 2020 World Bank-supported initiative involving Israel’s National Cyber Directorate and Toka Group, a cyber-intelligence company co-founded by Barak. The partnership was presented as contributing to Nigeria’s national cybersecurity framework, but Drop Site News argued it also deepened Israeli corporate access to sensitive security architecture.

In its conclusion, the investigation alleged that a network of security interventions, port negotiations, and technology investments enabled Epstein and Barak to profit from instability associated with the Boko Haram conflict, while simultaneously advancing Israeli commercial and strategic interests in Nigeria. The outlet stressed that these claims are based on document reviews and correspondence, framing them as allegations rather than established legal findings.

Epstein, Ex-Israeli PM Named in Alleged Profiteering From Boko Haram Crisis

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoCanada Opens New Express Entry Draw for Nigerian Workers, Others

-

Politics21 hours ago

Politics21 hours agoPeter Obi Launches ‘Village Boys Movement’ to Rival Tinubu’s City Boys Ahead of 2027

-

News3 days ago

News3 days agoKorope Drivers Shut Down Lekki–Epe Expressway Over Lagos Ban (Video)

-

News1 day ago

News1 day agoPolice to Arrest TikToker Mirabel After She Recants False Rape Claim

-

Health3 days ago

Health3 days agoRamadan Health Tips: Six Ways to Stay Hydrated While Fasting

-

Entertainment3 days ago

Entertainment3 days agoActress Destiny Etiko Breaks Silence on Alleged Nollywood Betrayal

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoEpstein, Ex-Israeli PM Named in Alleged Profiteering From Boko Haram Crisis

-

metro2 days ago

metro2 days agoOsun Awards 55.6km Iwo–Osogbo–Ibadan Road Project to Three Contractors