Opinion

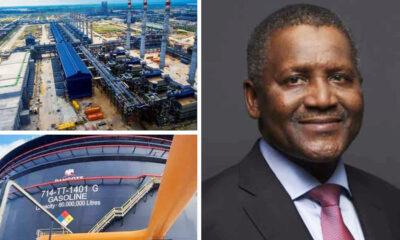

Farooq Kperogi: Conspiracy of price gouging between Dangote and NNPCL

Farooq Kperogi: Conspiracy of price gouging between Dangote and NNPCL

I had said to myself and to people close to me that I would never write again on the untenably rising prices of petrol in Nigeria because when I wrote column after column to presage the unfolding petrol-price-inspired cost-of-living tragedy, scores of people across the Nigerian political divide impassionedly disagreed with me because the presidential candidates to whom they abdicated their brains in 2023 also demonized “petrol subsidies” and promised to remove them.

But the extortionate prices Nigerians are still paying for petrol in spite of the well-justified hopes that the coming on stream of the Dangote Refinery would bring down prices—and the blindingly perplexing and never-ending cascade of blame games, accusations and counter-accusations between the Dangote Refinery and the Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited (NNPCL)—compelled me to revisit this issue.

There appears to be a well-choreographed conspiracy between the Dangote Refinery and the NNPCL to take advantage of Nigerians by keeping petrol prices unjustifiably high. This is somewhat similar to what we call price gouging in the United States.

Price gouging occurs when businesses calculatedly raise the price of goods, services, or commodities to an excessively high level, especially during a crisis or emergency when demand spikes and supply is limited. In the context of fuel, price gouging is said to occur if a company or companies sharply increase fuel prices in response to supply shortages.

Although price gouging typically happens during natural disasters, pandemics, or situations where essential goods become scarce, it can happen anytime. It is, in essence, the exploitation of consumers’ vulnerabilities during critical times. That’s what I suspect is happening in Nigeria now.

NNPCL is the sole buyer and distributor of fuel from the Dangote Refinery. It controls the supply chain and effectively excludes independent marketers from accessing the refinery’s output. That’s not free-market capitalism; that’s state capitalism. That’s not deregulation; it’s regulated deregulation.

But the Dangote Refinery’s price regime is also puzzling. Oil industry expert Mr. Dan Kunle forwarded to me a WhatsApp message that breaks down the landing cost of petrol per liter, which added up to N1107. I haven’t verified the accuracy of the claim, but I assume that it must have some credibility to deserve being forwarded by Mr. Kunle whose knowledge of the industry I have a deep admiration for.

READ ALSO:

- Edo poll: I’m still in the race, says LP candidate Akpata

- Abuja light train moved 250,000 passengers in 100 days – CCECC

- I didn’t come to Aso Rock for money but work – Tinubu

The message says “based on publicly available data,” which it admitted “are subject to change and may vary depending on market conditions, exchange rates, and other factors,” Dangote Refinery is exempt from incurring costs related to freight (N86.48), jetty depot (N15.35), storage (N12.58), financing (N34.67), foreign exchange (N23.45), NPA charges (N10.58), NIMASA charges (N5.29), and customs duties (N51.17), and therefore should, by my calculation, charge no more than N518.35 per liter.

So it’s a mystery how Dangote and NNPCL agreed on N766. If Dangote Refinery acquired its crude oil in dollars, did it also cover salaries and operational costs in dollars? Crude oil is just one part of the overall production cost.

What’s more concerning, perhaps, is that ₦766 per liter cost seems to be the expected price even after Dangote begins purchasing crude in naira from the NNPC. How can this be justified, especially when the additional costs associated with exporting crude and importing refined products would no longer apply once Dangote receives domestic crude from October 1st?

Additionally, as my friend Professor Moses Ochonu pointed out during our August 31 “Diaspora Dialogues” show titled “Who Wants to Kill Dangote Refinery and Why,” under existing laws, NNPC is supposed to supply its own refineries with 450,000 barrels per day, which was historically sufficient to meet local demand before those refineries became defunct.

That crude was never meant for export. It only started being exported after the refineries stopped functioning. So, as Professor Ochonu pointed out, why not simply allocate that crude to Dangote Refinery, paying only for the refining process plus a modest commission or profit, and then sell the refined products to Nigerians at more affordable rates?

This approach would involve some level of subsidy, but that’s how the system was intended to function when state-owned refineries were operational. In any case, in spite of the sustained propaganda against subsidies, every serious country on earth dispenses subsidies, including energy subsidies, to its citizens. Nigerians are entitled to a subsidy on a quarter of the country’s crude output, and subsidizing petrol makes sense because of its broad impact on the economy.

Moreover, this method would be far less costly than the inflated and fraudulent subsidies that have been paid for imported fuel over the years.

I am, of course, aware that Nigerians have allowed themselves to be willingly brainwashed into assuming that there is no nexus between “subsidy removal” and petrol price hike. I hope the truth is becoming apparent now.

For example, in my April 29, 2023, column titled “Six Agenda Items for Tinubu’s Success,” I wrote, among other things: “Don’t increase petrol prices by other names. I know that there is now an artfully manufactured consent, particularly among the gilded classes in Nigeria, about the undesirability of ‘fuel subsidy.’

“I don’t care what it’s called, but any policy (call it deregulation, subsidy removal, appropriate pricing, etc.) that results in an arbitrary and unbearable hike in the price of petrol without a corresponding increase in the salaries of workers and an improvement in the living conditions of everyday people will sink Tinubu.

READ ALSO:

- Adesanya bets $10,000 on Joshua to defeat Dubois

- Edo election: Mercy Johnson’s husband escapes assassination

- EFCC begins fresh hunt as Yahaya Bello goes into hiding

“No responsible government shies away from subsidizing the production and consumption of essential commodities for its people. I have lived in the United States, the belly of the capitalist beast, for nearly two decades, and I can tell you that governments at both federal and state levels heavily subsidize petrol consumption—in addition to agriculture.”

In response, a Facebook friend who was inebriated with anti-subsidy propaganda retorted in the comment section: “I beg to disagree on your advice of his administration not removing fuel subsidy which has become [a] cesspool of corruption…. I prefer he use resources saved from its removal on foodstuffs, health and educational facilities as well as increase salaries of workers which PMB has commenced to FG workers with the 40% peculiar allowance to its staff with effect from last January and which arrears was paid with April Salary. Other points raised are apt.”

“At this rate,” I replied sarcastically, “I pray petrol price gets to 1,000 naira per liter so that everyone will get a taste of what I’ve been talking about.”

“Speculation, speculation and speculation!” he shot back. “Govt should be encouraged to put the refineries in good shape and encourage more private investors to build more just as Dangote and Ishiaku Rabiu [sic] are doing. All refineries should be supplied crude oil in naira and not buying in international oil prices in American dollars. Market forces would later force the prices down if monopoly is not allowed to fester just as happened when telecommunication was privatised and mtn simcard was 30k, others like Mtel, Glo, etc forced the price down and now costs next to nothing.”

Two weeks ago, I reminded him of our April 29, 2023, conversation and asked if he still stood by his arguments and what he thought about the N1,000 per liter prediction I made, which he had dismissed as “speculation.” I am still awaiting his response as I write this.

Well, Nigerians were flushed with enthusiasm at the prospect of the operation of the Dangote Refinery. They expected it to help reduce fuel prices, but the monopolistic control of NNPCL and the caginess and opacity of Dangote Refinery itself have spawned a jarring disconnect between expectations and reality.

As I have repeatedly pointed out, Nigeria, as an oil-producing country, should not withhold the reasonable expectation that its citizens benefit from lower fuel prices. To suggest otherwise is akin to giving someone a handful of cream while allowing their skin to remain parched — an act of neglect that borders on cruelty. Nigerians could more easily reconcile with elevated petrol prices if their country were not blessed with abundant oil resources.

Denying citizens the fruits of their nation’s wealth is no different from a wealthy parent who starves their own children while justifying the neglect by pointing to the deprivation of their less fortunate neighbors. Such a parent is not only irresponsible but unworthy of the trust and care of their children.

Farooq Kperogi: Conspiracy of price gouging between Dangote and NNPCL

Farooq Kperogi is a renowned columnist and United States-based Professor of Journalism.

Opinion

El Rufai’s Arise News mind game with Ribadu, By Farooq Kperogi

El Rufai’s Arise News mind game with Ribadu, By Farooq Kperogi

El Rufai’s Arise News mind game with Ribadu, By Farooq Kperogi

Opinion

Oshiomhole: Behold the 13th disciple of Christ

Oshiomhole: Behold the 13th disciple of Christ

Opinion

AFCON 2025: Flipping Content Creation From Coverage to Strategy

AFCON 2025: Flipping Content Creation From Coverage to Strategy

By Toluwalope Shodunke

The beautiful and enchanting butterfly called the Africa Cup of Nations (AFCON) emerged from its chrysalis in Khartoum, Sudan, under the presidency of Abdelaziz Abdallah Salem, an Egyptian, with three countries—Egypt, Sudan, and Ethiopia—participating, and Egypt emerging as the eventual winner.

The reason for this limited participation is not far-fetched. At the time, only nine African countries were independent. The remaining 45 countries that now make up CAF’s 54 member nations were either pushing Queen Elizabeth’s dogsled made unique with the Union Jack, making supplications at the Eiffel Tower, or knocking at the doors of the Palácio de Belém, the Quirinal Palace, and the Royal Palace of Brussels—seeking the mercies of their colonial masters who, without regard for cultures, sub-cultures, or primordial affinities, divided Africa among the colonial gods.

From then until now, CAF has had seven presidents, including Patrice Motsepe, who was elected as the seventh president in 2021. With more countries gaining independence and under various CAF leaderships, AFCON has undergone several reforms—transforming from a “backyard event” involving only three nations into competitions featuring 8, 16, and now 24 teams. It has evolved into a global spectacle consumed by millions worldwide.

Looking back, I can trace my personal connection to AFCON to table soccer, which I played alone on concrete in our balcony at Olafimihan Street—between Mushin and Ilasamaja—adjacent to Alafia Oluwa Primary School, close to Alfa Nda and Akanro Street, all in Lagos State.

Zygmunt Bauman, the Polish-British sociologist who developed the concept of “liquid modernity,” argues that the world is in constant flux rather than static, among other themes in his revelatory works.

For the benefit of Millennials (Generation Y) and Generation Z—who are accustomed to high-tech pads, iPhones, AI technologies, and chat boxes—table soccer is a replica of football played with bottle corks (often from carbonated drinks or beer) as players, cassette hubs as the ball, and “Bic” biro covers for engagement. The game can be played by two people, each controlling eleven players.

I, however, enjoyed playing alone in a secluded area, running my own commentary like the great Ernest Okonkwo, Yinka Craig, and Fabio Lanipekun, who are all late. At the time, I knew next to nothing about the Africa Cup of Nations. Yet, I named my cork players after Nigerian legends such as Segun Odegbami, Godwin Odiye, Aloysius Atuegbu, Tunji Banjo, Muda Lawal, Felix Owolabi, and Adokiye Amiesimaka, among others, as I must have taken to heart their names from commentary and utterances of my uncles resulting from sporadic and wild celebrations of Nigeria winning the Cup of Nations on home soil for the first time.

While my connection to AFCON remained somewhat ephemeral until Libya 1982, my AFCON anecdotes became deeply rooted in Abidjan 1984, where Cameroon defeated Nigeria 3–1. The name Théophile Abéga was etched into my youthful memory.

Even as I write this, I remember the silence that enveloped our compound after the final whistle.

It felt similar to how Ukrainians experienced the Battle of Mariupol against Russia—where resolute resistance eventually succumbed to overwhelming force.

The Indomitable Lions were better and superior in every aspect. The lion not only caged the Eagles, they cooked pepper soup with the Green Eagles.

In Maroc ’88, I again tasted defeat with the Green Eagles (now Super Eagles), coached by the German Manfred Höner. Players like Henry Nwosu, Stephen Keshi, Sunday Eboigbe, Bright Omolara, Rashidi Yekini, Austin Eguavoen, Peter Rufai, Folorunsho Okenla, Ademola Adeshina, Yisa Sofoluwe, and others featured prominently. A beautiful goal by Henry Nwosu—then a diminutive ACB Lagos player—was controversially disallowed.

This sparked outrage among Nigerians, many of whom believed the referee acted under the influence of Issa Hayatou, the Cameroonian who served as CAF president from 1988 to 2017.

This stroll down memory lane illustrates that controversy and allegations of biased officiating have long been part of AFCON’s history.

The 2025 Africa Cup of Nations in Morocco, held from December 21, 2025, to January 18, 2026, will be discussed for a long time by football historians, raconteurs, and aficionados—for both positive and negative reasons.

These include Morocco’s world-class facilities, the ravenous hunger of ball boys and players (superstars included) for the towels of opposing goalkeepers—popularly dubbed TowelGate—allegations of biased officiating, strained relations among Arab African nations (Egypt, Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco), CAF President Patrice Motsepe’s curt “keep quiet” response to veteran journalist Osasu Obayiuwana regarding the proposed four-year AFCON cycle post-2028, and the “Oga Patapata” incident, where Senegalese players walked off the pitch after a legitimate goal was chalked off and a penalty awarded against them by DR Congo referee Jean-Jacques Ndala.

While these narratives dominated global discourse, another critical issue—less prominent but equally important—emerged within Nigeria’s media and content-creation landscape.

Following Nigeria’s qualification from the group stage, the Super Eagles were scheduled to face Mozambique in the Round of 16. Between January 1 and January 3, Coach Eric Chelle instituted closed-door training sessions, denying journalists and content creators access, with media interaction limited to pre-match press conferences.

According to Chelle, the knockout stage demanded “maximum concentration,” and privacy was necessary to protect players from distractions.

This decision sparked mixed reactions on social media.

Twitter user @QualityQuadry wrote:

“What Eric Chelle is doing to journalists is bad.

Journalists were subjected to a media parley under cold weather in an open field for the first time in Super Eagles history.

Journalists were beaten by rain because Chelle doesn’t want journalists around the camp.

Locking down training sessions for three days is unprofessional.

I wish him well against Mozambique.”

Another user, @PoojaMedia, stated:

“Again, Eric Chelle has closed the Super Eagles’ training today.

That means journalists in Morocco won’t have access to the team for three straight days ahead of the Round of 16.

This is serious and sad for journalists who spent millions to get content around the team.

We move.”

Conversely, @sportsdokitor wrote:

“I’m not Eric Chelle’s biggest supporter, but on this issue, I support him 110%.

There’s a time to speak and a time to train.

Let the boys focus on why they’re in Morocco—they’re not here for your content creation.”

From these three tweets, one can see accessibility being clothed in beautiful garments. Two of the tweets suggest that there is only one way to get to the zenith of Mount Kilimanjaro, when indeed there are many routes—if we think within the box, not outside the box as we’ve not exhausted the content inside the box.

In the past, when the economy was buoyant, media organisations sponsored reporters to cover the World Cup, Olympics, Commonwealth Games, and other international competitions.

Today, with financial pressures mounting, many journalists and content creators seek collaborations and sponsorships from corporations and tech startups to cover sporting events, who in turn get awareness, brand visibility, and other intangibles.

As Gary Vaynerchuk famously said, “Every company is a media company.” Yet most creators covering AFCON 2025 followed the same playbook.

At AFCON 2025, most Nigerian journalists and content creators pitched similar offerings: on-the-ground coverage, press conferences, team updates, behind-the-scenes footage, analysis, cuisine, fan interactions, and Moroccan cultural experiences.

If they were not interviewing Victor Osimhen, they were showcasing the stand-up comedy talents of Samuel Chukwueze and other forms of entertainment.

What was missing was differentiation. No clear Unique Selling Proposition (USP). The result was generic, repetitive content with little strategic distinction. Everyone appeared to be deploying the same “Jab, Jab, Jab, Hook” formula—throwing multiple jabs of access-driven content in the hope that one hook would land.

The lesson is simple: when everyone is jabbing the same way, the hook becomes predictable and loses its power.

As J. P. Clark wrote in the poem “The Casualties”, “We are all casualties,” casualties of sameness—content without differentiation. The audience consumes shallow content, sponsors lose return on investment, and creators return home bearing the “weight of paper” from disappointed benefactors.

On November 23, 1963, a shining light was dimmed in America when President John F. Kennedy was assassinated.

As with AFCON today, media organisations sent their best hands to cover the funeral, as the who’s who of the planet—and if possible, the stratosphere—would attend. Unconfirmed reports suggested that over 220 VVIPs were expected.

While every newspaper, radio, and television station covered the spectacle and grandeur of the event, one man, Jimmy Breslin, swam against the tide. He chose instead to interview Clifton Pollard, the foreman of gravediggers at Arlington National Cemetery—the man who dug John F. Kennedy’s grave.

This act of upended thinking differentiated Jimmy Breslin from the odds and sods, and he went on to win the Pulitzer Prize in 1986.

Until journalists and content creators stop following the motley and begin swimming against the tide, access will continue to be treated as king—when in reality, differentiation, aided by strategy, is king.

When every journalist and content creator is using Gary Vaynerchuk’s “Jab, Jab, Jab, Hook” template while covering major sporting events, thinkers among them must learn to replace one jab with a counterpunch—and a bit of head movement—to stay ahead of the herd.

Toluwalope Shodunke can be reached via tolushodunke@yahoo.com

-

metro3 days ago

metro3 days agoIKEDC Sets Feb 20 Deadline for Customers to Submit Valid IDs or Face Disconnection

-

Education3 days ago

Education3 days agoSupreme Court Affirms Muslim Students’ Right to Worship at Rivers State University

-

metro2 days ago

metro2 days agoLagos Police Launch Manhunt for Suspect in Brutal Ajah Murder

-

News2 days ago

News2 days agoAso Rock Goes Solar as Tinubu Orders National Grid Disconnection

-

Business3 days ago

Business3 days agoNaira Could Trade Below ₦1,000/$ With Dangote Refinery at Full Capacity — Otedola

-

metro3 days ago

metro3 days agoArmy University Professor Dies in Boko Haram Captivity After Nearly One Year

-

International3 days ago

International3 days agoTrump Halts Minnesota Immigration Crackdown After Fatal Shootings, Protests

-

Sports2 days ago

Sports2 days agoLookman Shines as Atlético Madrid Hammer Barcelona 4-0